The global population is expected to reach 8 to 9 billion by 2050, with 70 percent of people concentrated in cities and slums. This will lead to increased pressure on local water resources, stemming from greater withdrawals and pollution. Globally, it will lead to increased water withdrawals for food, energy and industrial production. An already competitive water landscape will become even more so. Usage will be stretched to the limit, and tensions will arise between countries that depend on a shared source of water.

The global population is expected to reach 8 to 9 billion by 2050, with 70 percent of people concentrated in cities and slums. This will lead to increased pressure on local water resources, stemming from greater withdrawals and pollution. Globally, it will lead to increased water withdrawals for food, energy and industrial production. An already competitive water landscape will become even more so. Usage will be stretched to the limit, and tensions will arise between countries that depend on a shared source of water.

In the developed world, access to water will put new, job-creating investments at risk and impact and increase the cost of water for everyone. In the United States, the EPA has already cited that areas in 36 states are facing water shortages. Health, too, can be an issue. According to the New York Times, “more than 20 percent of America’s water treatment systems have violated key provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act over the last five years.”

In the developed world, access to water will put new, job-creating investments at risk and impact and increase the cost of water for everyone. In the United States, the EPA has already cited that areas in 36 states are facing water shortages. Health, too, can be an issue. According to the New York Times, “more than 20 percent of America’s water treatment systems have violated key provisions of the Safe Drinking Water Act over the last five years.”

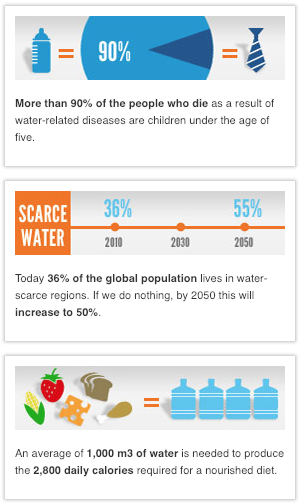

In the developing world, poor access to water will not only constrict economic growth, it will completely stifle it, contributing to disease and malnutrition and keeping women and youth from the classroom or the workforce.

Clearly, in big ways, small ways and in ways we don’t often consider, water is a quality of life issue – both in the developed and developing worlds. And no matter where we live, providing a reliable, safe and sanitary supply of water determines the health of both individuals and entire communities.

Clearly, in big ways, small ways and in ways we don’t often consider, water is a quality of life issue – both in the developed and developing worlds. And no matter where we live, providing a reliable, safe and sanitary supply of water determines the health of both individuals and entire communities.